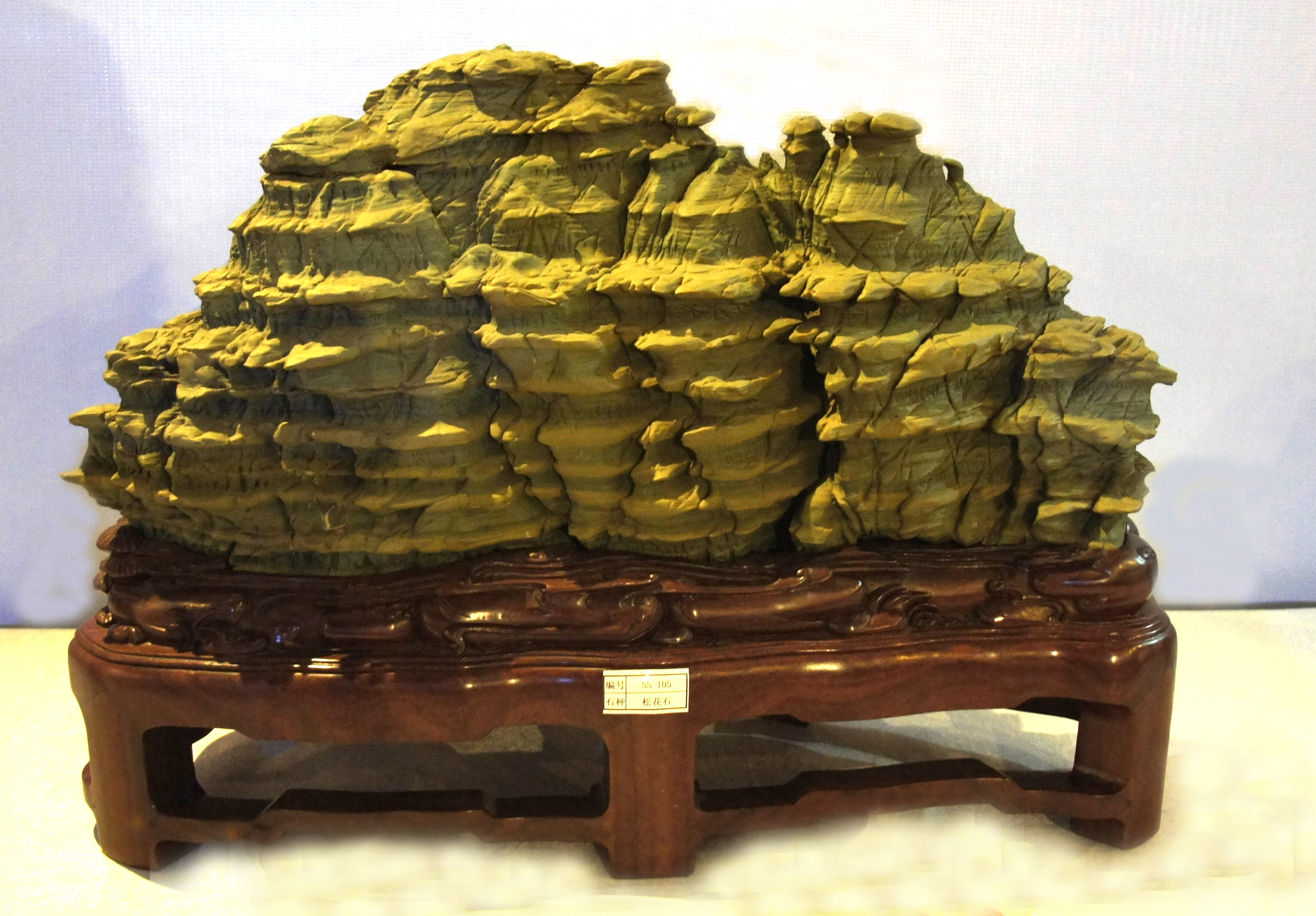

Nowadays the classification systems by shape and origin are more or less recognized and used in different Asian countries as well as in the West (America, Australia, Africa, Europe). There are also many subcategories of the classification by shape, for example landscape stones are subdivided into distant and near view mountain stones, plateau, terrace or step stones, mountain-stream, waterfall, water pool, rain shelter, cave, island, coastal, reef stones…

Stones, symbol of steadfastness and durability, were always collected by men.

Extraordinarily shaped stones were highly estimated respectively venerated mainly in Asia where stone veneration has a long tradition and where it is known under different names: in Japan such stones are called Suiseki, in China under other as Shangshi (evaluated stones), in Taiwan as Yea-Shyr or Yasek (elegant stones) and in Korea as Suseok (stones of longevity or eternity). Originally Suiseki represent natural landscape scenes.

Apart from this there are many other terms for such stones in Japan as well as in China and Korea, the original countries of stone culture.

Since Europeans learned first from the Japanese about this special stone veneration respectively the art form of beautiful natural stones in the second half of the 20th century the name “Suiseki” became established in Europe.

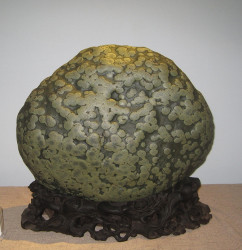

These artistic natural stones, also called Viewing Stones, are influenced by stylistic periods (in the same way) as other fine arts. The traditional Chinese Scholars’ rocks, also called spirit stones or ‘gong shi’ (= respected stones) in Chinese, were mainly appreciated at the Song, Ming and Qin dynasties. Nowadays figure and colour stones are appreciated mainly in China.

Landscape stones, distant view (click images for slideshow)

Landscape stones, shelter

Landscape stones, waterfall

Landscape stones, waterpool

Object stones

Abstract shape stones

Surface pattern stones

Colour stones

Beautiful stones, so called biseki, which are worked on (cut and/or polished)

History

Chinese Scholars’ Rocks

China is birthplace of stone culture. Stones were always collected for different reasons. They were used as tools but also venerated for religious, commemorative or aesthetic purposes. Since the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) there are evidences that Chinese used large stones to embellish their gardens and courtyards. Literati and artists brought smaller stones of unusual shape into their studios. This way they brought the nature into their studio because stones were regarded as an incarnation of vital energy, “Kernels of Energy, Bones of Earth” (title of a treatise about the rock in Chinese Art by John Hy) so the stones represented a microcosm of the whole universe on which the scholar could meditate and admire the wonders respectively beauty of nature. Stones are symbols of harmony between men and nature. In early times such stones where placed in basins, later mounted on carved wooden stands and displayed on desks, tables or bookshelves and larger ones were set directly on the floor.

The “Golden Age” of Scholars’ Rocks was the Tang (690 - 908) and Song (960 – 1279) dynasty.

Gongshi is the Chinese term for “an elegant stone for a scholars’ studio”, simply called “Chinese Scholars’ Rocks” or “Spirit rocks” in English.

Four stone types are regarded as classical Scholars’ Rocks, all hard limestones:

1. Lingbi stones from Anhui province

Lingbi stone of elegant movement resembling a dancer, 39 cm h, Richard Sang collection

Lingbi stone, The Landscape of Cliff to the Skies, 129 x 84 x 47 cm, Baocheng Museum, Tianjin, China (photo taken 2007, BCI VIP tour)

2. Ying(de)stones from Guangdong

Lingbi stone, The Landscape of Cliff to the Skies, 129 x 84 x 47 cm, Baocheng Museum, Tianjin, China (photo taken 2007, BCI VIP tour)

Ying or Yingde stone, origin: Guangdong province, China, photo taken 2015 during BCI tour to Yingde

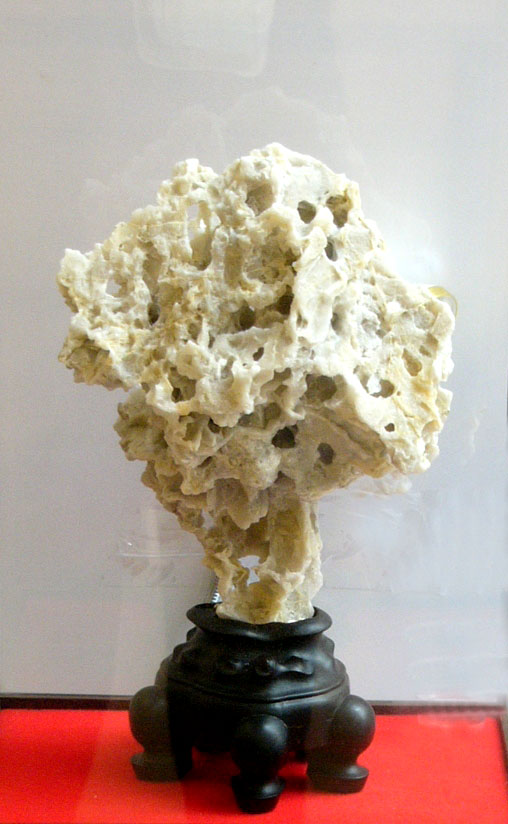

3. Taihustones from Tai lake in Jinagsu

Taihu stone, h: 54 cm, origin: Jiangsu province, China, Benz collection

Red Taihu stone, origin: Jiangsu province, China, wooden stand 9 cm h in Jiangnan style, collection of Museum of East Asian Arts in Berlin

4. Kunstones from Shandong

Kun stone, exhibited at “The Second Shanghai Duolun International Master Stone Collectors Exhibition on Invitation”, in Shanghai 2016

The Chinese calligrapher, painter, poet and stone lover Mi Fu 1051 – 1107) established four judging criteria for scholars' stone appreciation:

Shou – thin and elegant

Zhou – wrinkled, with grooves, interesting surface texture

Lou – with holes, channels, openings

Tou - openness, wind and light can pass through holes or channels.

Lou and Tou are closely related.

Suiseki in Japan

Stone appreciation originated in China. It was spread from China to Korea and Japan since the 6th century. In the following centuries Japan was politically closed several times to the outside world. Therefore the admiration of extraordinary stones developed in a different and separate way in Japan and was at first only popular among cultivated Zen monks, tea masters and the samurai class mainly since the Muromachi period (1333 – 1573), Edo (1600 – 1868) and Meji period (1868 – 1911). They preferred subdued colours and simple (‘quite’) shape. Deep black stones were and still are considered as ideal. This kind of stones is best suitable for meditation or contemplation.

The term Suiseki is only about 150 years old. The literal meaning is “water stones” (sui = water, seki = stone). According to some people, this made allusion to their formation by water, respectively the forces of nature.

According to Nippon Suiseki Association (NSA) “the word Suiseki is an abbreviation of the term sansui keiseki, which roughly translates as ‘landscape view stone’ or ‘landscape scenery stone’.”

Nowadays Suiseki are more popular among all social classes and often regarded as a hobby or leisure pursuit

Wooden stands, suiban, doban

In ancient time, stones were displayed on brocade tissue, on cushions or in vessels filled with sand. Nowadays there are mainly two different ways to secure stones in their position:

- the placement on wooden stands, called daiza in Japan

Suiseki with restrained “simple” wooden stand (daiza)

- the positioning in a suiban, a flat rectangular or oval ceramic tray, or a doban, a metallic tray or vessel, mainly of bronze.

Island stone in a suiban. Normally, the suiban should be about twice the size of the stone. AIAS exhibition in Cesano Maderno, Italy 2017

Ibigawa ishi in a rectangular doban at the NSA Suiseki exhibition on occasion of the 8th WBFF convention in Saitama, Japan in 2017

There is a remarkable contrast between China and Japan regarding the preferred positioning of a stone. Whereas in China the vertical alignment predominates, in Japan most suiseki are aligned horizontally. The stand should underline the value respectively beauty of a stone. They are made of “noble” wood and artistically crafted. The design concept of wooden stands differs also between Chinas and Japan. Japanese daiza are custom made, restrained respectively plain fitting exactly the stone on the base so they don’t overpower the stone which should be predominant for the observer. In general, Chinese wooden stands are more elaborate, partly lavishly carved. Only excellent wood is used for excellent stones: Redwood, Chickenwing wood, Ebony, different kinds of Rose wood as well as Zitan wood. There are three different styles in China which give no exact indication of the geographic origin or location but simply denote a stylistic preference:

- the northern style: horizontally oriented, resembling Japanese daiza

Dahua stone on a wooden stand of northern style, exhibited in Guangzhou in 2015

- Jiangnan or Suzhou style

Lingbi stone on a wooden stand of Jiangnan or Suzhou style, exhibited in Shanghai 2006

There are two different kinds: firstly relatively high stands with added curved leggs (see Chinese Scholars’ rocks) and symbolic carvings of cloud-like or Lingshi mushroom motifs.

Ying stone on a table-like wooden stand of Jiangnan style, exhibited in Guangzhou in 2015

Secondly table-like stands with indentations on the surface to take the stone and hold it in position.

Wuling stone on a table-like wooden stand (Jiangan style), exhibited in Guangzhou in 2015

- Southern style: artistically shaped carvings with naturalistic motifs related to the thematic of the stone.

Green Lentil stone on a wooden stand in southern style with wave carving, exhibited in Guangzhou in 2015

Viewing Stones on exhibit

There are differences between a display at home (in a private house), in a tokonoma of a traditional Japanese house, in a museum or in public exhibitions. The intention is always to creating a scene, convey the season, an atmosphere or feeling, a philosophical background. This is created by different “tools”: the kind of chosen accessories, their shape, size (proportions) and colour. As a rule: not more than two or three objects should be display in an arrangement. “Less is more”! When you bring nature (a stone) in your house and display it in your tokonoma you have to create space. This way you are able to create space for your imagination, to create a microcosm.

Repetition should be avoided. When using for example a rectangular suiban don’t add a plant in a rectangular pot (use instead an oval, round or handmade irregular pot). A calligraphy should emphasize the meaning of the display. It should evoke a philosophical background or indicate the season. Don’t display calligraphies where the character of stone features. Slim, small sized scrolls (fig. 31) are well suited for exhibitions, but should be used sparingly. Large and long scrolls are suited for a tokonoma display. The scroll should not reach the floor (tatami mat).

The following aspects are important:

1. theme of the display respectively the intention of the exhibitor:

- greeting a guest

- indication of the season

- indication of where the object was found

- connection with a mythological, philosophical, historical or artistic background

2. correct placementof the objects

3. direction of flow/movementof the objects

4. balance and harmonybetween the exhibited object (accent plant, table, stand, shelf, wooden board, mat, art object, scroll…) regarding shape, size, proportions, colour.

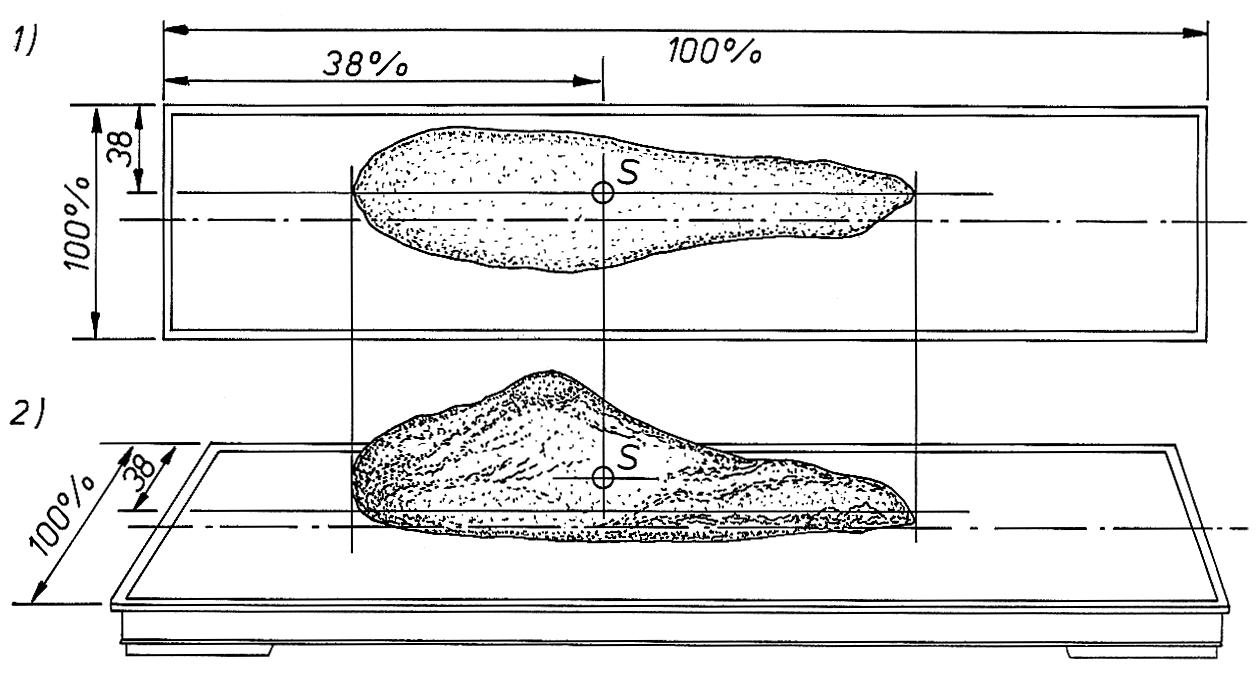

Placement of a viewing stone in a suiban or doban follows the rules of the Golden Section. The direction of flow goes to the larger space.

Drawing by Willi Benz in “Bonsai Kusamono Suiseki – A Practical Guide for Organizing Displays with Plants and Stones”: 1) view from above, 2) front view

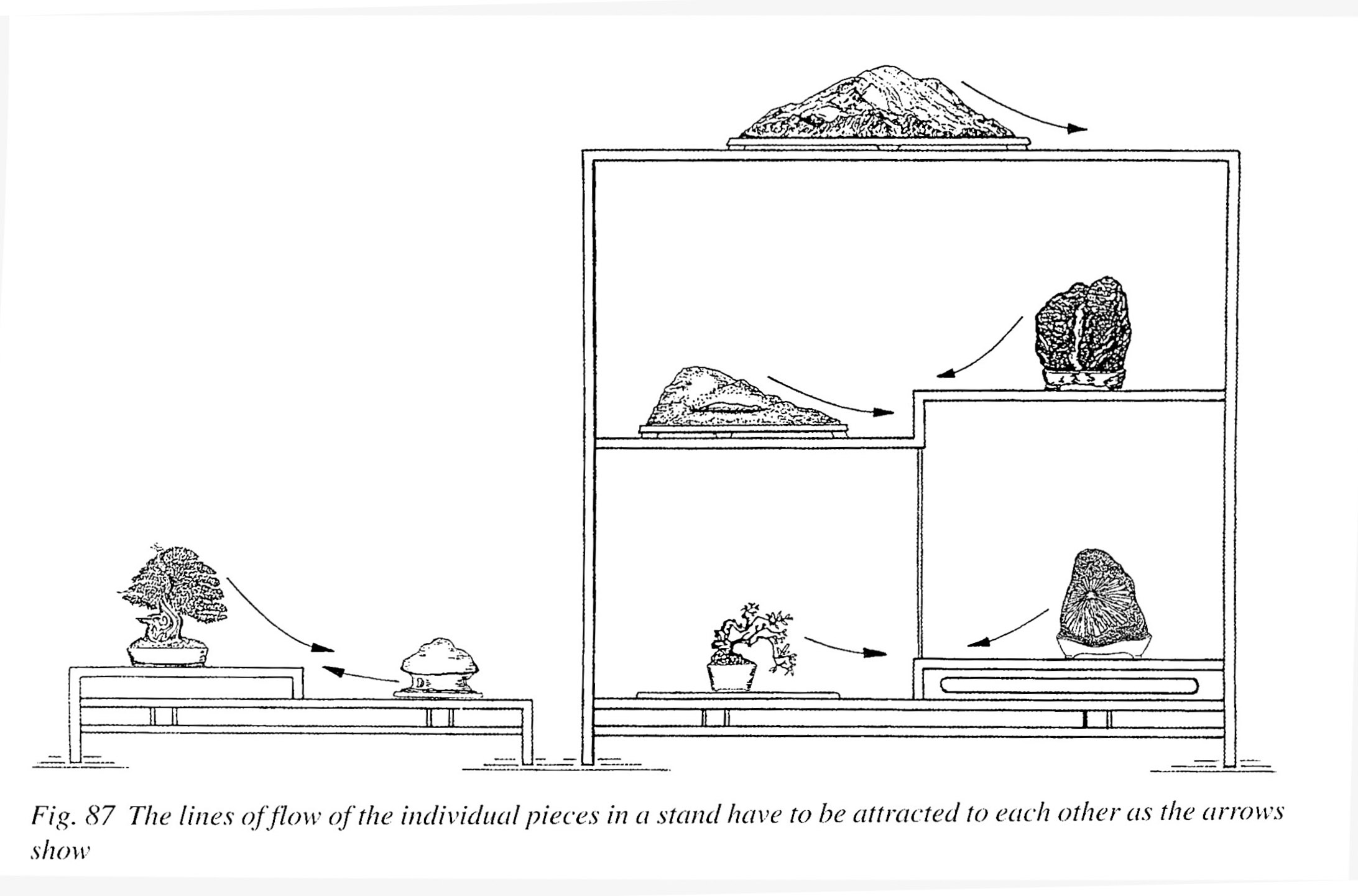

Items in exhibit should correspondent with each other:

The lines of flow of the individual pieces in a stand have to be attracted to each other as the arrows show. Drawing by Willi Benz in “Bonsai Kusamono Suiseki – A Practical Guide for Organizing Displays with Plants and Stones”, available from Gudrun Benz

Suiseki and Viewing Stones

By Gudrun Benz, Germany

Viewing Stones are an art form of extraordinary stones shaped (only) by nature and displayed indoors.

Their characteristics / features are:

- extraordinary shape with suggestive power

- minimum hardness

- characteristic surface texture

- characteristic colour

- harmonious overall impression of the presentation, balance

- age as a collecting object

Classification by shape: we distinguish between:

- landscape stones

- object stones

- abstract shape stones

- surface pattern stones

- colour stones

- beautiful stones, so called biseki, which are worked on (cut and/or polished)

Apart from the classification by shape there are others, for example by origin, surface pictures or texture. The classification by origin is quite often used too. In Japan the terms Kamogawa ishi, Sajigawa ishi, Setagawa ishi, Furuya ishi, Sado Akadama ishi, Kutaro ishi for example indicate rivers or regions/areas. ‘Ishi’ means stone. Kamo, Saji, Seta are rivers, Furuya is a province, Sado an island, Kutaro is a town on Hokaido island. In China the terms Red river stone, Lingbi stone, Ying(de) stone, Dahua stone… also indicate the location where these stones are found. In Europe Ligurian stones are found in the province of Liguria, Italy, etc.

More on Classifications

Nowadays the classification systems by shape and origin are more or less recognized and used in different Asian countries as well as in the West (America, Australia, Africa, Europe). There are also many subcategories of the classification by shape, for example landscape stones are subdivided into distant and near view mountain stones, plateau, terrace or step stones, mountain-stream, waterfall, water pool, rain shelter, cave, island, coastal, reef stones.

History

China is birthplace of stone culture. Stones were always collected for different reasons. They were used as tools but also venerated for religious, commemorative or aesthetic purposes. Since the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) there are evidences that Chinese used large stones to embellish their gardens and courtyards.Literati and artists brought smaller stones of unusual shape into their studios. This way they brought the nature into their studio because stones were regarded as an incarnation of vital energy.

Stone Display

In ancient time, stones were displayed on brocade tissue, on cushions or in vessels filled with sand. Nowadays there are mainly two different ways to secure stones in their position.

How to display your Viewing Stones

There are differences between a display at home (in a private house), in a tokonoma of a traditional Japanese house, in a museum or in public exhibitions. The intention is always to creating a scene, convey the season, an atmosphere or feeling, a philosophical background. This is created by different “tools”.